2018

State of the Sites

By ExchangeMonitor Publications & Forums

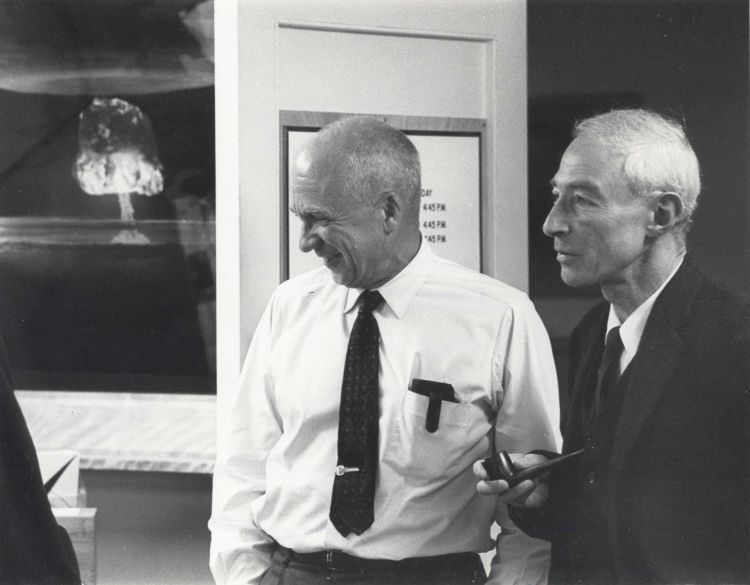

Over a period of decades starting in World War II, the United States carried out a massive undertaking to create a nuclear weapon and then turn a handful of bombs into an arsenal designed to keep the country safe through the Cold War. One legacy of that endeavor is a set of highly contaminated facilities that contributed to production and upkeep of the nuclear stockpile, spread across the United States.

Some of these sites – Los Alamos in New Mexico, Oak Ridge in Tennessee, and Hanford in Washington state – were there at the beginning of this program in the Manhattan Project. Others were built up in following decades.

Since 1989 it has been the job of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management to remediate these properties for future use. By numbers alone it could be said to be in the home stretch of its mission: cleanup is complete at 91 of 107 sites, from Amchitka Island, Alaska, to the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, New Jersey.

But that would not tell the whole story, as a straight count leaves the most challenging projects that are years if not decades from completion. For example: The Hanford Site, covering 586 square miles in southeastern Washington, is counted as the most contaminated nuclear facility in the United States following decades of plutonium production for the nation’s defense. The remediation program covers more than 40 facilities and projects, a mix of historic structures and those established to address that history. The cleanup is expected to be the most expensive and longest-lasting at the Energy Department: costing up to about $150 billion and wrapping up as late as 2075.

The entire DOE Environmental Management life cycle is forecast to cost anywhere from $369 billion to $414 billion. It will encompass thousands of personnel and scores of companies, from global engineering and construction giants assigned to manage an entire project to local subcontractors brought on for a specific job.

The ExchangeMonitor’s Weapons Complex Monitor has been tracking developments in this business for nearly three decades, about as long as the Office of Environmental Management has existed. We’ve been the go-to resource for the latest in the cleanup complex, whether it is the most recent milestone in remediation or the behind-the-scenes changes at companies and their government client. This will remain our mission.

In this publication, State of the Sites, we’re trying something a bit different: Offering readers a distilled, up-to-date snapshot of the status of the 16 ongoing cleanup programs. Each article will offer a succinct history of these facilities contribution to history and where they stand now. More than that, they’ll discuss the business going forward – who’s in on new contracts, who’s out, and what opportunities are on the horizon.

We hope you find this publication useful both today and in the future.

Brookhaven National Laboratory, New York

The Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, N.Y., like a number of other national labs operated by the Department of Energy, is both an active research facility and a site of nuclear cleanup overseen by DOE’s Office of Environmental Management.

The History

The laboratory opened in 1947 in the hamlet of Upton as a research center for non-military uses of the atom. Today it is managed by Brookhaven Science Associates, a partnership of Battelle and Stony Brook University under the oversight of DOE’s Office of Science, with a staff of close to 3,000 conducting research in areas ranging from energy security to QCD matter.

Environmental remediation at Brookhaven is conducted under the 1992 Federal Facilities Compliance Agreement, negotiated by DOE, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the New York state Department of Environmental Conservation.

Some major cleanup projects have been completed in the past 26 years, including removal of mercury contamination from the nearby Peconic River and several soil projects. Sixteen groundwater treatment systems were installed that by 2012 had extracted 6,950 pounds of volatile organic compounds from an area aquifer.

The focus of environmental management operations in recent years has been on decontamination and decommissioning of two reactors at Brookhaven: the High Flux Beam Reactor and the Graphite Research Reactor.

Today

The funding and contracting situation for cleanup at Brookhaven appears largely dormant at the moment.

The Office of Environmental Management’s latest acquisition forecast, current as of Jan. 3, 2018, includes no listings for Brookhaven. The office’s August 2017 listing of major procurements also did not feature any upcoming contracts at the laboratory.

Brookhaven, which is listed among several “small sites” in DOE’s annual budget for non-defense environmental cleanup, received no funding for this work in fiscal 2016 and 2017. The department proposed to boost that to $2 million for fiscal 2019, to be used for ongoing planning for demolition of the High Flux Beam Reactor stack.

The stack has proven to be a challenge: Once used for exhaust from the Graphite Research Reactor, its teardown was funded through the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Work started in 2010, and then stopped later that year due to safety issues.

Work at Brookhaven is scheduled to be complete in 2020, according to the latest DOE projection, which has a 50 to 80 percent confidence level. The total environmental management life-cycle cost forecast for Brookhaven ranges from $486 million to $491 million.

Image: Brookhaven Lab Flickr.

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Hanford Site

For nearly 43 years the Hanford Site in the desert of eastern Washington state produced plutonium for the nation’s nuclear weapons program. That required a vast industrial complex, which is now massively contaminated and will require decades, thousands of workers, and tens of billions of dollars to resolve in one of the world’s largest nuclear cleanup programs.

The History

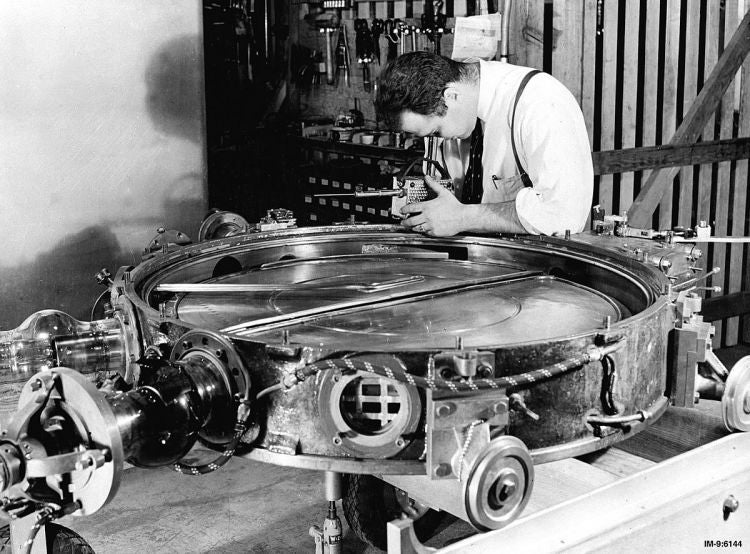

Starting with the Manhattan Project, the U.S. government built at Hanford nine plutonium production reactors, five processing plants, and hundreds of support, research, and uranium fabrication facilities.

By the time plutonium production stopped at the end of the Cold War, large amounts of radioactive and hazardous chemical waste had been buried on site and 440 billion gallons of contaminated liquid had been dumped into the soil or injected into groundwater.

The environmental cleanup of the 586-square-mile complex is expected to last decades longer than the site was used to produce plutonium. Close to $50 billion has been spent since cleanup began in 1989. The most recent Hanford life-cycle cost report calls for an additional $107 billion in spending through about 2060, but critics say the estimate is low.

Progress has been made in more than 28 years of cleanup. Roughly 18 billion gallons of contaminated groundwater have been cleaned and much of the remediation of the 220 square miles of the Columbia River Corridor has been finished. In addition, two high-risk projects are nearing completion. Most of the Plutonium Finishing Plant has been demolished after nearly two decades of preparation. At the K Reactor Basins, about 2,300 metric tons of stored irradiated fuel have been removed and 38 cubic yards of radioactive sludge have been consolidated in underwater containers, with removal of the sludge beginning in June 2018.

But only limited remediation of the Central Plateau has been completed, and only a couple gallons of the 56 million gallons of radioactive waste left from chemically processing irradiated fuel to remove plutonium have been treated. The Waste Treatment Plant, once planned to be fully operational to vitrify much of the tank waste in 2011, now is not expected to reach that milestone until 2036.

Today

Most of Hanford’s major contracts are set to expire between the end of the current fiscal year and 2020. The Energy Department’s acquisition strategy calls for awarding five new contracts, covering most work except for construction of the Waste Treatment Plant. The contracts would be similar to existing contracts, including deals of up to 10 years for Hanford Mission Essential Services, Tank Waste Cleanup, and Central Plateau Cleanup. Smaller contracts would be awarded for Hanford Occupational Medicine Services and 222-S Laboratory Services.

With decades of environmental remediation remaining at Hanford, budgets that have ranged from about $2 billion to $2.4 billion in recent years will not be sufficient to meet legal obligations, according to regulators and stakeholders. The Trump administration has proposed a Hanford budget for fiscal 2019 of $2.185 billion.

That would encompass $1.438 billion for the Office of River Protection, $61 million below current spending for the Hanford operation that manages waste storage tanks and the Waste Treatment Plant; and $747 million for the Richland Operations Office, a $169 million cut for the manager of site-wide services at Hanford and all cleanup other than the waste storage tanks.

About half of the total federal budget for Hanford is needed to keep the site safe and pay for support services and infrastructure maintenance, said Alex Smith, manager of the Nuclear Waste Program for the Washington state Department of Ecology, a Hanford regulator alongside the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“But as the lack of adequate funding continues to be a reason to delay cleanup, the maintenance and service piece of the budget will continue to increase as well, through inflation and the simple fact that it costs more to maintain deteriorating and aging facilities,” Smith said. “If the overall budget for Hanford remains flat, less and less money will be available for cleanup activities.”

Idaho Site

Established to encompass the Naval Proving Ground and surrounding land in eastern Idaho, the Idaho Site has in its time housed 52 nuclear research and materials testing reactors. Today it remains home to the Idaho National Laboratory and a number of cleanup and waste management programs, two of which face key deadlines by the end of 2018.

The History

The Idaho National Laboratory is the latest of several names for a research facility dating to the early years of the Cold War. Building on 271 square miles already used as the Naval Proving Ground, the Atomic Energy Commission in 1949 began developing the National Reactor Testing Station, where the first of the 52 reactors achieved criticality in 1951.

In 1974, the facility was renamed the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory to reflect an expanded research mission. It then became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory in 1997 and finally the Idaho National Laboratory in 2005.

Today the Idaho Site covers 890 square miles of Arco Desert land above the Snake River Plain Aquifer. The lab continues its mission of advancing nuclear energy, among other programs, even as the federal government addresses the legacy left by decades of military and energy activities, including reactor operations, spent fuel reprocessing, and lab research.

Among the challenges: Remediation of hundreds of contaminant releases generated by waste discharges, spills, industrial injection wells, and wastewater disposal ponds built without liners.

Today

Environmental remediation at the Idaho Site had for years been broadly divided into two contracts: the Idaho Cleanup Project and the Advanced Mixed Waste Treatment Project, both managed by the DOE’s Office of Environmental Management and regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Idaho Department of Environmental Quality.

In 2016, Fluor Idaho received a contract valued at $1.4 billion over five years to consolidate the work into the Idaho Cleanup Project Core Contract. Its broad mission covers environmental cleanup, including protection of the Snake River Plain Aquifer; operation of the Advanced Mixed Waste Treatment Project for extraction, processing, and shipment of transuranic and low-level wastes; and bringing online the years-overdue Integrated Waste Treatment Unit to convert 900,000 gallons of liquid radioactive waste into a solid form for storage.

The fiscal 2018 omnibus funding plan signed into law about halfway through the budget year provides $434 million for cleanup and waste disposition, community and regulatory support, and excess facilities decontamination and disposition at INL. That was $84 million above the DOE request and almost as much more than the $359 million the department is seeking for fiscal 2019. The Idaho National Laboratory Environmental Management program life cycle is estimated at $18.7 billion to $21.4 billion, with completion projected from 2045 to 2060.

A 1995 settlement agreement between Idaho, DOE, and the Navy established a number of requirements for cleanup at the site, including: shipment of all spent fuel from Idaho; treatment of all high-level waste at INL, by 2035; and shipping all transuranic waste from the site by the end of 2018.

The state and federal governments subsequently went to federal court over transuranic waste from the Rocky Flats Plant in Colorado that was shipped to Idaho and interred in the Surface Disposal Area. A federal court in 2006 ruled that the 1995 settlement requires DOE to remove the waste, and the mandate was formalized in a 2008 agreement between the state and DOE.

The Energy Department has acknowledged that it might miss the deadline this year to ship all transuranic waste out of Idaho, largely due to the nearly three-year closure of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico following a February 2014 radiation release. Idaho had as of mid-2017 shipped 53,000 of 65,000 cubic meters of waste by mid-2017, and has been the top shipper to WIPP since it reopened in early 2017.

The state has also fined DOE millions of dollars for its failure to meet the 2012 deadline to begin operating the IntegratedWaste Treatment Unit. The facility was completed that year, but has not yet functioned as intended. The Energy Department has said operations could begin this year.

Images: Idaho National Laboratory Flickr

Images: Idaho National Laboratory Flickr

Images: Idaho National Laboratory Flickr

Images: Idaho National Laboratory Flickr

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

The U.S. Energy Department’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California today operates from two locations: the original site, spread over more than 1 square mile about 45 miles east of San Francisco; and the 7,000-acre Site 300 high-explosive test range near the city of Tracy. Both are now Superfund sites.

Over the years, about 18,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil have been dug up at LLNL Site 300. Much of the waste was taken to off-site locations for disposal, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Energy Department is also sustaining aging, contaminated buildings that stopped operating years ago but have yet to enter decontamination and decommissioning.

The History

Lawrence Livermore was established in 1952, in the early years of the Cold War, to advance nuclear weapons technology. In the 1950s it helped design thermonuclear warheads that could be launched by submarines. Decades later it would help define the U.S. Stockpile Stewardship Program. Site 300 also dates to the 1950s as a weapons research facility.

Lawrence Livermore remains active in the research and development of nuclear weapons, and other national security activities under the direction of DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration, while also coordinating cleanup with the Office of Environmental Management.

Decades of weapons and explosive testing contaminated soil and groundwater. The main site was placed on the Superfund list in 1987, followed by Site 300 three years later.

Cleanup of the main property began in 1995. Twenty-one facilities for groundwater and soil extraction and treatment are currently operating at Site 300. Tri-Valley CAREs, an advocacy group, has said LLNL cleanup will be “multi-generational,” lasting more than 50 years. The life-cycle cleanup costs for cleanup of LLNL is expected to be in excess of $500 million, according to the fiscal 2019 DOE budget justification. The department is seeking $1.7 million for this work in the upcoming budget year.

Today

The lab is managed for the NNSA by Lawrence Livermore National Security (LLNS), a partnership of the University of California, Bechtel National, BWXT Technology, AECOM, and Battelle. Cleanup is typically carried out by LLNS and its subcontractors.

In the Department of Energy’s fiscal 2019 budget proposal, Livermore and the Y-12 National Security Complex in Tennessee would split $150 million toward cleanup up nonoperating “excess facilities.”

The excess facilities at LLNL were built between 1952 and 1980 for research, and they remain contaminated by radiological material and chemical hazards, such as beryllium. In some cases, the facilities could fail during an earthquake.

During 2018 and 2019, DOE is conducting studies involving perchlorate contamination, groundwater contamination, and related problems around retired Buildings 812, 850, and 865, which were used in explosive testing operations. The planning is being done in connection with the U.S. EPA and the state of California. A major concern is remediation of the depleted uranium contaminated soil at the Building 812.

Another facility of concern, discussed in recent budget documents, is the Pool Type Reactor at LLNL, which was used for nuclear weapons research and radiation studies, and ceased operation around 1980.

Los Alamos National Laboratory

The Los Alamos National Laboratory, located 25 miles northwest of Santa Fe, N.M., is a leading center for U.S. nuclear weapons research and stockpile management. It is also managing a legacy of radioactive and hazardous waste built up since the early 1940s.

The History

Los Alamos began its life in 1943 as Site Y of the Manhattan Project with a mission to develop an atomic bomb that could be powered by nuclear material from other sites. The Energy Department took over ownership of the 35-square-mile property from the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in the mid-1970s, and its mission has grown to encompass a broad range of national security research.

Decades of nuclear weapons testing and nuclear research have resulted in contamination of soil, water, and buildings at Los Alamos, which DOE has been cleaning up over time.

The University of California managed the laboratory from 1943 until 2006, when the operations contract was assumed by Los Alamos National Security (LANS) – a team encompassing the university, Bechtel, BWX Technologies, and AECOM. Until recently, the management and operations contractor also conducted environmental remediation at the site.

In 2014, DOE decided to split off legacy cleanup from the management and operations contract. The move occurred after a drum of radioactive waste from the lab burst open in February 2014 at the Energy Department’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) near Carlsbad, N.M., closing the transuranic waste disposal facility for nearly three years.

Since 1989, environmental cleanup at LANL has included removal and disposal of contaminated soil; remediating groundwater; and disposition of legacy waste; along with tearing down and decontaminating facilities at Technical Area 21, where plutonium research occurred during the Cold War.

More than 50 percent of the legacy cleanup has been completed at 2,100 sites targeted for chemical or radioactive waste remediation. This includes tearing down 28 buildings and installing a regional groundwater monitoring well in Technical Area 21.

The Energy Department says 93 percent of the transuranic waste stored above ground at Los Alamos has been removed. Over 4,000 TRU waste containers have been removed in recent years.

Today

Newport News Nuclear BWXT-Los Alamos (N3B) is the new legacy cleanup provider at Los Alamos, taking the reins in April on a potential 10-year, $1.39 billion contract.

The award covers a host of cleanup and waste management operations at the lab, including surface and groundwater monitoring and compliance, meeting the terms of a 2016 federal-state consent order on remediation, and drafting interim and permanent solutions for a hexavalent chromium plume.

The site is regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and New Mexico Environment Department.

The DOE Office of Environmental Management budget for the Los Alamos National Laboratory was funded at $220 million in fiscal 2018. For fiscal 2019, DOE requested $192 million; the House Appropriations Committee recommended $198 million and the Senate Appropriations Committee offered $220 million.

A major 2019 effort will be planning for eventual retrieval and repackaging of the site’s below-grade transuranic waste, which will include the evaluation and recommendation regarding disposition of 33 remote-handled transuranic waste shafts.

Recent budget projections have environmental remediation at LANL wrapping up in 2036, with a life-cycle cost between $6.2 billion and $7.3 billion.

Images: Los Alamos National Laboratory

Moab UMTRA, Utah

The Department of Energy is more than halfway through the process of relocating 16 million tons of uranium mill tailings from a site about 3 miles from Moab, Utah, via the Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) Project.

The History

From 1956 to 1984, the Uranium Reduction Co. and later Atlas Minerals Corp. produced “yellowcake” uranium concentrate for U.S. national defense and then commercial nuclear power operations, leaving behind 16 million tons of a “sand-like material” that contains radium and other radioactive elements in a pile spread over roughly 130 acres.

The Energy Department is responsible for disposal of the material, which involves excavating the tailings and drying them on-site, then shipping them by train in steel containers to a final disposal facility at Crescent Junction, Utah, about 30 miles north of the Moab UMTRA site.

More than $325 million has been spent since excavation began in April 2009.

Today

As of April 2018, 56 percent of the tailings had been removed.

Portage Inc., an engineering firm based in Idaho Falls, Idaho, in April 2016 received a five-year, $153.8 million follow-on task order through November 2021 to continue excavating and transporting the mill tailings. It secured its first contract in November 2011, worth $121.2 million, replacing Utah-based EnergySolutions.

More recently, DOE in August 2017 retained S&K Logistics Services, of Byron, Ga., as the technical assistance contractor for the project, under a five-year contract worth up to $24.5 million.

Funding has been an issue for the project, with Portage reportedly laying off more than 30 workers in April 2016. The Energy Department for fiscal 2019 requested $34.9 million for Moab under its non-defense environmental cleanup budget line item – down nearly $3 million from the fiscal 2018 continuing resolution that was in place at the time of the latest budget request.

Locals hope to secure more funding from DOE to increase the rate of shipments – which are down from four per week to two -- and claw back the completion date for the project, which was set at 2019 under the 1978 Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act. That date has since fallen back to 2025 and now 2034, said Lee Shenton, Grand County’s former liaison to the project. The total life-cycle cost is estimated at roughly $1.9 billion.

“An extra $10 million a year at Moab could double the rate of shipments and finish off the project in the mid-2020s, and would barely be noticed at Hanford,” according to Shenton.

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Nevada

The Nevada National Security Site, perhaps better known as the Nevada Test Site that hosted hundreds of atmospheric and underground nuclear blasts, is among a small number of Department of Energy properties undergoing environmental remediation while sustaining a national security mission. As of 2018, hundreds of distinct sites within the facility remain to be remediated and closed.

The History

In the early years of the Cold War, President Harry Truman designated a 1,375-square-acre expanse of desert north of Las Vegas for use in testing the nation’s growing nuclear arsenal. First called the Nevada Proving Grounds, the site hosted 928 nuclear tests from 1951 to 1992, when the United States voluntarily suspended its program of trial explosions.

After nuclear testing ended, the Department of Energy projected that in excess of 300 curies of radioactivity remained at the Test Site, spread across the soil, existing facilities, and groundwater. In 1996, the state of Nevada and the U.S. Energy and Defense departments agreed on a federal facility agreement and consent order designating the federal government’s responsibilities for environmental remediation of that contamination at the Nevada National Security Site, the Tonopah Test Range, the Central Nevada Test Area, the Project Shoal Area, and the Nevada Test and Training Range.

The scope of environmental restoration encompassed analysis and remediation of roughly 900 locations used for underground nuclear testing, 100 surface or shallow contamination areas, and over 1,100 “industrial-type” sites.

Today

As of the publication of the Energy Department’s latest budget request, the EM Nevada Program still covered 868 sites of contaminated groundwater and 15 contaminated soil and industrial sites, along with monitoring of remediated locations and management of the Nevada Radioactive Waste Management Complex.

Navarro Research and Engineering holds the current $64.3 million contract, through Jan. 31, 2020, for the Nevada Environmental Services Program. The Energy Department is in the early stages of selecting the next contract holder, with a draft request for proposals issued in July 2018. An early industry day for the next contract attracted a number of companies familiar with the DOE cleanup complex, including Navarro, Atkins, CH2M, Leidos, and Veolia.

For fiscal 2019, the Department of Energy requested $60.1 million for defense environmental cleanup at Nevada, down by about $2 million from the enacted amount for fiscal 2017.

The DOE environmental management life-cycle cost for the Nevada National Security Site is estimated at $2.6 billion. Work is expected to be complete by 2030.

Oak Ridge Reservation

The history of the Oak Ridge Reservation in Tennessee dates to the Manhattan Project and through the Cold War. Today it remains home both to active operations for the U.S. nuclear deterrent and a large-scale environmental remediation program, covering the former Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant, the Y-12 National Security Complex, and parts of Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The Oak Ridge facility is on the EPA National Priority List of Superfund sites and is the focus of one of the largest environmental cleanup efforts in the country. At the state level, it is regulated by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.

The U.S. Energy Department expects to complete cleanup at the Gaseous Diffusion Plant by 2020, after which its Office of Environmental Management (EM) will shift resources to Y-12. Completion dates for cleanup work at Y-12 and Oak Ridge National Laboratory are yet unclear. In its fiscal 2019 budget justification. DOE lists 2046 as the completion date for the environmental management project.

The History

Starting as the Clinton Engineer Works during World War II, Oak Ridge grew over the decades into a complex encompassing five gaseous diffusion buildings that produced enriched uranium for nuclear weapons. One of those buildings, K-25, was for a time the world’s largest building at 1.64 million square feet.

Oak Ridge halted uranium enrichment in 1985, but the Y-12 National Security Complex continues to manufacture nuclear weapons components and by 2025 is scheduled to house a new Uranium Processing Facility priced at up to $6.5 billion.

Nuclear arms operations left hundreds of facilities at Y-12 and the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant contaminated with hazardous or radioactive materials including mercury, beryllium, technetium, and industrial waste. Hazards from asbestos and animal droppings inevitable to old buildings also remain.

Meanwhile, contamination from Manhattan Project and Cold War-era reactor experiments and enriched uranium storage at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory continues to require costly maintenance and surveillance.

Cleanup at Oak Ridge largely began in the 1990s under the then-new DOE Office of Environmental Management. From 1994 to fiscal 2017, DOE spent $11.6 billion decommissioning and demolishing contaminated buildings on the reservation, remediating soil and shipping high-level waste off for disposal.

Remediation prime URS-CH2M Oak Ridge (UCOR) has been on the job since 2011, after securing a $2.2 billion contract for five years, plus a four-year option period.

Today

With the five gaseous diffusion buildings on the site already demolished, EM must only complete a few remaining demolition projects and remediate the soil before the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant, now called the East Tennessee Technology Park, can be turned over to the city of Oak Ridge for reindustrialization and commercial use.

The groundbreaking of Y-12’s Mercury Treatment Facility in November opens the door for demolition of excess facilities on the plant site. Once constructed, the Outfall 200 Mercury Treatment Facility will allow EM to demolish mercury contaminated buildings without contaminating local waterways. The Energy Department has said the facility will be able to treat 3,000 gallons of contaminated water per minute and to collect up to 2 million gallons of storm water.

GEM Technologies, of Knoxville, is conducting site preparation for the facility, and DOE in March issued a request for proposals for a construction contractor.

Among the advances in recent years at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, DOE’s Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management (OREM) in 2017 completed disposition of about 1,100 containers of uranium-233 that had originated at the Indian Point 1 reactor in New York. OREM also last year stabilized ORNL’s old radioisotope laboratory, and is continuing asbestos abatement, building contaminant characterization, and waste disposal work elsewhere at the lab.

The Energy Department is seeking another cleanup contractor to demolish other buildings on the site and construct a new CERCLA (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act) low-level radioactive waste landfill. The contract is estimated to cost between $2 billion and $5 billion over the next 10 years

The Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management has an annual budget of nearly $500 million, distributed in defense, uranium enrichment, and non-defense spending accounts. Of that, roughly $280 million in defense spending funded cleanup at Y-12 and ORNL in the 2017 enacted budget. Another $213 million to fund work at the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion plant came from the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund that covers work at DOE’s Oak Ridge, Portsmouth, and Paducah sites.

Under the Trump administration’s latest budget request, Oak Ridge cleanup would take about a $90 million cut. It is unclear which specific areas the cut would affect.

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant

The Energy Department’s Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Kentucky is one of three sites, all now retired, that provided uranium enrichment for the nation’s defense needs. Operations at the McCracken County site were centered within about 650 acres of a larger 3,500-acre complex.

More than a half century of uranium enrichment operations produced hazardous wastes, radioactive wastes, and various types of mixed wastes. Since the 1980s, DOE cleanup efforts at Paducah have included treatment of 4 billion gallons of water contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE), disposing of roughly 6 million cubic feet of waste, and tearing down 43 facilities.

The History

The Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant was built in the 1950s on the site of a World War II munitions plant to enrich uranium for U.S. nuclear weapons. Its mission was later modified to include uranium enrichment for commercial nuclear power plants.

The United States Enrichment Corp. (now Centrus Energy) managed the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant after the federal government privatized its uranium enrichment function in July 1998. The company ceased enrichment operations at Paducah in 2013.

As a result of the large amounts of waste and groundwater contamination over the years, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listed Paducah as a Superfund site in 1994. Since 1990, DOE has spent more than $2 billion on cleanup, which is guided by a federal facility agreement between the department, the EPA, and the state of Kentucky.

Today

The Energy Department in recent years has awarded a number of contracts to advance environmental remediation at Paducah.

Four Rivers Nuclear Partnership, the CH2M-led venture with Fluor and BWX Technologies, in 2017 secured a deal worth up to $1.5 billion over a decade for deactivation and remediation at Paducah, covering facility characterization and stabilization, tearing down and removing old structures, and other responsibilities.

Mid-America Conversion Services, a partnership led by SNC-Lavalin subsidiary Atkins, with Westinghouse and Fluor, has a five-year, $318 million contract through January 2022 for conversion of depleted uranium hexafluoride (DUF6) at Paducah and DOE’s Portsmouth Site in Ohio. The Energy Department plans by 2032 to convert about 740,000 metric tons of the material into hydrofluoric acid and uranium oxide for reuse or disposal.

Kentucky-based Swift and Staley won a DOE support services contract for Paducah in June 2015. The contract, which has a three-year base and a 22-month extension option, has a full potential value of $177.2 million. It involves a slew of infrastructure and support services including facility maintenance, records maintenance, janitorial services, snow removal, safeguards and security and training.

The Trump administration budget request for fiscal 2019 would fund Paducah cleanup at roughly $270 million. The Energy Department estimates its environmental management project at the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant will be complete from 2065 to 2070 at a life-cycle cost of $34.9 billion to $41.1 billion.

In August 2017, the three federal facility agreement parties committed to focus the next 10 years on the investigation and remediation of the C-400 Complex, which cleaned parts and equipment used in enrichment. Over time the building leaked trichloroethylene, which is a major source of groundwater contamination at Paducah. A DOE record of decision on how to demolish and clean up the site is currently expected in fiscal 2022.

One key challenge includes 30,000 pounds of uranium deposits in the Paducah process equipment, which needs to be removed before remediation, according to DOE.

Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant

The Energy Department’s Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Pike County, Ohio, is one of three retired plants that enriched uranium for the U.S. nuclear weapons program. Operations were conducted on about 1,200 acres of a larger 3,777-acre property, selected by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in 1952.

Its mission switched in the 1960s to enriching uranium for nuclear power. In all, the site hosted uranium enrichment from the mid-1950s until 2001. This work left hazardous chemical and radioactive wastes.

The DOE Office of Environmental Management became responsible for cleanup of both Portsmouth and its partner gaseous diffusion site in Paducah, Ky., in 1989. Work completed to date includes removal of more than 37,000 gallons of trichloroethylene (TCE) from groundwater, tearing down 37 structures, and shipping 119 million pounds of waste offsite for disposal. The federal agency also reports 23,000 metric tons of depleted uranium hexafluoride (DUF6) has been converted into a more stable chemical form prior to disposal or reuse.

The History

The gaseous diffusion plants in Ohio and Kentucky were privatized by the Energy Policy Act of 1992. A private company, USEC, now known as Centrus Energy, ceased enrichment at Portsmouth in 2001. Decommissioning and decontamination started in 2010.

During the Obama administration, the Energy Department provided D&D contractor Fluor-BWXT Portsmouth with transfers of government-owned natural UF6 to help supplement the cost of Portsmouth remediation. The uranium barter program was suspended by DOE in 2018 at the urging of Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), who said the practice hurt the uranium market in his home state.

Today

Completion of Portsmouth remediation has been targeted for 2039-2041, with a life-cycle environmental management cost of $17.5 billion to $18.5 billion, according to recent DOE projections.

The Energy Department is completing the transfer of the first tract of Portsmouth land back to private use for economic development. An 80-acre parcel, which was once an air landing strip, is being conveyed to the Southern Ohio Diversification Initiative, the reuse organization for the site. A second tract could be transferred in fiscal 2019.

The Energy Department is developing an on-site disposal cell planned to open by 2022 for 2 million cubic yards of waste from building demolition at Portsmouth. Despite pushback from local governing bodies, DOE says the facility will be a boon by leaving only 400 acres under perpetual environmental care, rather than potentially the entire 1,200 acres. That would be accomplished by elimination of several on-site landfills.

Upcoming challenges at Portsmouth will include dismantling and remediation of three major 1950s-era process buildings: X-326, X-333, and X-330. Portsmouth and Paducah together must also convert a combined inventory of nearly 800,000 metric tons of DUF6 into a more stable form.

There are several major contracts in place for Portsmouth.

Fluor-BWXT Portsmouth has a $3.4 billion D&D contract dating to 2011. The current 30-month option period expires at the end of September.

Professional Project Services (Pro2Serve) subsidiary Enterprise Technical Assistance Services (E-TAS) was awarded a contract in June for up to five years and $137 million for technical support services for the Portsmouth/Paducah Project Office. That award was protested to the Government Accountability Office, but the protest was dismissed when DOE agreed to reconsider the procurement.

Mid-America Conversion Services, which is led by SNC-Lavalin subsidiary Atkins, with partners Westinghouse and Fluor, has a $318.8 million contract, which started in February 2017 and runs through January 2022, to operate deplete uranium hexafluoride conversion facilities at Portsmouth and Paducah.

Portsmouth Mission Alliance has a $140 million infrastructure services contract that runs from March 2016 to, potentially, January 2021. The first extension period is due in March 2019. PMA is comprised of North Wind and Swift and Staley. The contract covers operations including security, records management, fleet management, and snow removal.

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: Sandia Labs Flickr

Images: Sandia Labs Flickr

Images: Sandia Labs Flickr

Images: Sandia Labs Flickr

Sandia National Laboratories

The Sandia National Laboratories is under new management and in the home stretch of its cleanup mission. As of 2017, more than 300 of 314 environmental remediation sites had been remediated at the sprawling facility on Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, N.M.

The History

The Sandia National Laboratories grew out of Z Division, formed in 1945 as a component of the nearby Los Alamos National Laboratory. Its initial mission involved ordnance development and production, and has grown to encompass national security operations including development of non-nuclear parts for nuclear weapons and defenses against terrorism involving weapons of mass destruction.

For much of its life, Sandia was managed by American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T), with Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin) taking over in 1993. Lockheed’s wholly owned subsidiary, Sandia Corp., was itself replaced in early 2017 by the Honeywell-led National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia.

Much like its older sibling to the north, Sandia’s operations have contaminated the ground on which it sits and regional groundwater. This includes, according to the 2004 state-federal consent order governing cleanup at the lab site: a host of solid and hazardous wastes and other contaminants, including lead, mercury, chromium, trichloroethylene (TCE), and polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB).

The DOE Office of Environmental Management provides funding for environmental management, while the semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration funds long-term stewardship. Dating to fiscal 1996, those budget line items have paid out just shy of $329 million for work at Sandia, with another $54.7 million baselined through fiscal 2028.

The New Mexico Environment Department is the primary regulator for the state hazardous waste program, including work at Sandia, under the auspices of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Today

Cleanup at the lab property is governed by a 2004 consent order between the New Mexico Environment Department, Department of Energy, and then-contractor Sandia Corp. By February 2018, NMED had listed 303 of 314 cleanup sites at Sandia as “corrective action complete.” That left 11 locations, with work deferred on three until a later date, according to the Department of Energy fiscal 2019 budget request.

Sandia’s management contractor is also in charge of cleanup, under its contract with DOE’s semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration rather than the department’s nuclear cleanup branch.

The department is asking for $2.6 million in fiscal 2019 for soil and water remediation. The environmental management program life cycle cost for Sandia is estimated at $284 million to $285 million, with completion anticipated in 2028.

“After cleanup is complete, the lab’s environmental obligations will include: continued compliance with environmental regulations applicable to ongoing operations; continued protection of human health and the environment; and continued environmental monitoring, maintenance, and long-term stewardship,” according to the lab. “Future cleanup sites are not anticipated, but if any environmental releases occur or past releases are discovered, DOE and the lab’s operating contractor will notify NMED and proceed with corrective action in accordance with the applicable requirements.”

Santa Susana Field Laboratory

The California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) is nearing the end of its lengthy planning process prior to remediation of chemical and radioactive waste contamination at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL), a 2,849-acre property located 30 miles from Los Angeles. The Department of Energy leased a 472-acre section of the site, making it one of the three responsible parties for its cleanup.

The History

Boeing and the federal government own the Simi Valley site, which was home to rocket engine tests and nuclear energy research for more than five decades, to the early 2000s.

The DOE footprint encompasses the Energy Technology Engineering Center (ETEC), within Area IV. The ETEC was the Department of Energy’s laboratory for nuclear power and liquid metal research. Operation of the agency’s experimental low-power nuclear reactors and fuel facilities released chemicals and radionuclides into soil, bedrock, and groundwater at the site and the adjoining Northern Buffer Zone. While DOE does not own any land at SSFL, it owns many buildings. Over the years the department has removed more than 200 buildings. Only 18 buildings remain, with about 75,000 square feet of material that must be either disposed of or recycled.

In 1990, California lawmakers authorized DTSC to act as the lead agency to oversee environmental remediation at Santa Susana. A 2010 consent order directed both the state and federal agencies to complete cleanup studies before work starts. Previously, it was anticipated DOE would wrap up soil work in 2017.

In a draft environmental impact statement issued in 2017, the Energy Department said its cleanup efforts could include tearing down its 18 remaining structures, remediation of soil and groundwater, and disposal of the resulting waste. Soil remediation alone could cost $3 million to $468 million, based on which option is eventually selected.

Today

The Energy Department started some interim groundwater measures in November 2017. By the fourth quarter off this year, the state expects to finish reviewing DOE’s long-term plan for improving groundwater. In April, DOE and the other two responsible parties started baseline air monitoring at Santa Susana. The tests are designed to gauge the amount of pollution prior to dust being stirred up by cleanup.

In its fiscal 2019 budget request, DOE asked for just over $8 million for environmental management operations at ETEC. That would be down by more than $2 million from recent budgets. Program milestones for fiscal years 2018 and 2019 include completion of the final environmental impact statement, finishing a groundwater corrective measure study and interim measures, and begin decontamination and decommissioning of site buildings and soil remediation.

The program completion date is listed as TBD in the latest DOE budget proposal, which cites a life-cycle cost of $345 million to $361 million. When work is done the land would be returned to Boeing.

The state expects environmental remediation to begin in 2019 and to wrap up in 2034. Like so many major cleanup projects, Santa Susana has been beset by missed deadlines due in part to the environmental complexity of the task. The rugged terrain is also a factor, California has said.

In 2014, North Wind won a contract of up to $25 million and five years, with extensions, for monitoring and decontamination and decommissioning work. CDM has a $11.3 million contract, signed in 2014, for National Environmental Policy Act work at ETEC.

Savannah River Site

The U.S. Department of Energy believes it could take up to 47 more years to complete processing and disposal of 35 million gallons of radioactive liquid waste at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. Along with converting the waste into a form safe for permanent storage, that will include closing 49 storage tanks and eventually decommissioning the treatment facilities themselves.

The History

Built in the 1950s near the city of Aiken, the 310-square-mile Savannah River Site was originally called the “bomb plant” because it was used to make nuclear weapons during the Cold War.

That mission ended in 1988 as the Cold War approached its end. The facility was left with more than 35 million gallons of highly radioactive liquid waste, stored in 49 underground carbon-steel storage tanks. That is the “single biggest environmental threat” in South Carolina, according to the state Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC), one of the Savannah River Site’s regulators along with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The Savannah River Site has closed eight of the 49 underground tanks since July 1997, and has treated roughly 3 million gallons of radioactive waste. Waste treatment includes converting sludge waste – which makes up about 10 percent of the waste volume – into a glassy, less harmful form at the Defense Waste Processing Facility (DWPF) for safe storage. The canisters will eventually be sent to an off-site repository for permanent disposal.

The other 90 percent of the material is salt waste, which since 2008 has been converted into a form suitable for permanent storage on-site using a pilot process. The site had been expected in December 2018 to start up the Salt Waste Processing Facility (SWPF), which will catapult liquid waste processing from 1.5 million gallons per year to 6 million. But DOE and contractor Parsons have acknowledged they will not meet that schedule.

The Savannah River Site handles other waste forms, including transuranic (TRU) waste – equipment, clothes, and other materials that have been contaminated with radioactive isotopes during work at the site. That material is periodically shipped to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) near Carlsbad, N.M., for permanent disposal.

Today

The Energy Department continues to work on closing the remaining 41 tanks, while SRS vies for adequate funding to complete the mission.

The Savannah River Site received about $766 million for waste cleanup in fiscal 2017, and roughly the same amount on an annualized basis in fiscal 2018 to date via a series of short-term spending measures. The Energy Department is seeking nearly $1.7 billion for environmental management operations at Savannah River for fiscal 2019.

Rick McLeod, president of the advocacy group SRS Community Reuse Organization, said he hopes Congress shows a stronger commitment this year. In fiscal 2017, SRS was the only DOE site to receive less proposed funding in Congress than what was suggested in the White House budget.

“This is unacceptable and does not meet our definition of an adequate and stable budget for expedited cleanup,” McLeod said. “We want to see significant advancement in SRS activities not just maintaining minimum conditions.”

Overall, the Energy Department believes SRS waste cleanup will be completed by 2065 and cost between $97 billion and over $115 billion.

The Energy Department in October 2017 awarded a new liquid waste management contract, worth up to $4.7 billion over 10 years, to Savannah River EcoManagement, a partnership of BWX Technologies, Bechtel National, and Honeywell International. But the Government Accountability Office upheld a protest from one of the losing bidders, a partnership of AECOM and CH2M. As a result, DOE has extended Savannah River Remediation’s contract through up to March 31, 2019, while it sorts out the contract dispute.

Savannah River Nuclear Solutions (SRNS) manages and operates the site under a $9.5 billion contract that expires on July 31, 2019. Currently, the Energy Department is in the acquisition planning stage of identifying a new contractor, meaning it is speaking with all of the interested parties and weighing the options. It is unclear on when the agency will submit an offer for the contract.

Images: Savannah River Site Flickr

Images: Savannah River Site Flickr

Images: Savannah River Site Flickr

Images: Savannah River Site Flickr

Images: Savannah River Site Flickr

Images: Savannah River Site Flickr

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Separations Process Research Unit

The Department of Energy is just a couple years away from completing environmental remediation of another one of its nuclear sites – the Separations Process Research Unit (SPRU) in Schenectady County, N.Y., though there were some bumps along the way.

The History

Built at the beginning of the Cold War, SPRU had a particularly short lifespan for its original mission: conducting experiments from 1950 to 1953 on extracting plutonium from irradiated uranium.

The facility, co-located with the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory, consisted of two primary buildings: the G2 process research site and the H2 waste processing building, along with related outbuildings and other infrastructure. When its research mission ended, Knolls (under the Department of Energy’s Office of Naval Reactors) used G2 for office space while H2 remained operational for waste processing. That ended in 1999, after which DOE began site characterization ahead of disposition operations.

The facility’s limited operational life resulted in radioactive contamination of nuclear facilities, along with groundwater and roughly 30 acres of land used for waste storage. The Energy Department-managed cleanup is overseen by New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation, with support from the state Department of Health and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Washington Group International received a task order in December 2007 for decontamination and demolition of the SPRU facilities, along with soil removal and shipping of the waste off-site. The company had just been acquired by URS Corp., which itself was bought out in 2014 by global engineering company AECOM, which holds the current contract for SPRU cleanup.

The Energy Department has touted a number of cleanup milestones since then, including removal of the last waste tank at the end of 2015, completion of demolition of the above-ground portion of the G2 building in November 2016, and initiating the last phase of demolition in fall 2017. Demolition of H2 and G2 wrapped up in May 2018.

Today

The Energy Department is also requesting a state permit for storage of mixed transuranic waste from SPRU at Knolls until it can be shipped to DOE’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, which is not anticipated before 2021.

The contract AECOM inherited in acquiring URS in 2014 requires the company to complete work even if the project has exceeded the cost cap set by the Energy Department. For fiscal years 2016 and 2017, DOE requested no funding from Congress for the project because that limit had been exceeded, though AECOM has taken legal steps to reclaim the money.

For fiscal 2019, which begins on Oct. 1, the Energy Department requested $15 million. The DOE budget justification lists completion of cleanup at the site in 2021.

West Valley Demonstration Project

Once a commercial nuclear fuel reprocessing facility, the West Valley Demonstration Project is housed in a 3,300-acre site owned by New York state in the town of Ashford. The radioactive waste and contaminated structures are within 200 acres at the site.

The site is being cleaned up in two phases. The first, which should be complete by 2030, covers demolition and off-site disposal of most above-ground facilities. The Energy Department and the state are preparing a supplemental environmental impact statement that will lay out the path for dealing with facilities expected to remain after Phase 1.

The History

Nuclear Fuel Services reprocessed spent reactor fuel 40 miles south of Buffalo for about six years in the 1960s and early 1970s, closing in 1972. The 1980 West Valley Demonstration Project Act made DOE responsible for tearing down old structures and solidifying and disposing of the radioactive waste left by the reprocessing operations.

The legislation stipulated DOE pay 90 percent of the cost, with the rest provided by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), which owns the property.

Since 1980, DOE and the state have together spent about $3.2 billion on remediation. In total, 275 canisters of vitrified high-level waste have been moved from a storage area in the main plant process building to a new on-site, dry cask storage building, according to the Energy Department.

The agency has removed 49 surplus facilities, more than 6 miles of piping, 50 tons of equipment, and 23,000 square feet of asbestos. In addition, 125 spent nuclear fuel assemblies have been shipped to the Idaho National Laboratory.

Demolition of the vitrification plant, which converted West Valley’s radioactive waste into a glass form for disposal, started in September 2017 and is more than 55 percent nearly complete.

Legacy processing and shipment was due for completion in September 2018. Deactivation of the Main Process Plant Building is 82 percent complete and demolition should begin this year, according to the contractor.

Most Phase 1 decommissioning waste will go to the Nevada National Security Site and the EnergySolutions low-level radioactive waste disposal facility in Clive, Utah. Some has been taken to the Waste Control Specialists site in Texas.

In August 2011, CH2M Hill BWXT West Valley LLC won an 8.6-year, $461.4 million contract from DOE for Phase I decommissioning. Cleanup areas remaining after Phase 1 will include the waste tank farm and a disposal area licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Today

Phase 1 completion by 2030 is a decade longer than DOE and the state envisioned in an environmental impact statement issued in 2010. The 2020 timeline was based on annual funding at $75 million, but the federal appropriation has been closer to $60 million for years, say state and local officials. The 2030 timeline would suggest an additional prime cleanup contract will be needed.

West Valley did get $75 million in funding in the final fiscal 2018 omnibus, more than the $66 million included in the fiscal 2017 enacted budget. The agency asked for $60 million for fiscal 2019.

The total Environmental Management life-cycle cost for West Valley is estimated at just under $1.9 billion to slightly over $2 billion, with completion forecast from 2040 to 2045.

A key issue to be decided in the supplemental EIS will be how much waste will be kept on-site, said Ashford Town Supervisor Charles Davis III. There is currently no federal repository available for high-level radioactive waste, so it could stay at West Valley indefinitely. “I want it all dug up and I want it all taken out of my town,” Davis said, though he acknowledged that might not be realistic.

State and local officials also want transuranic waste at West Valley classified as defense-related rather than its current commercial designation. Such a change would offer clarity to the disposal path for the material, according to officials from New York.

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Images: U.S. Department of Energy

Waste Isolation Pilot Plant

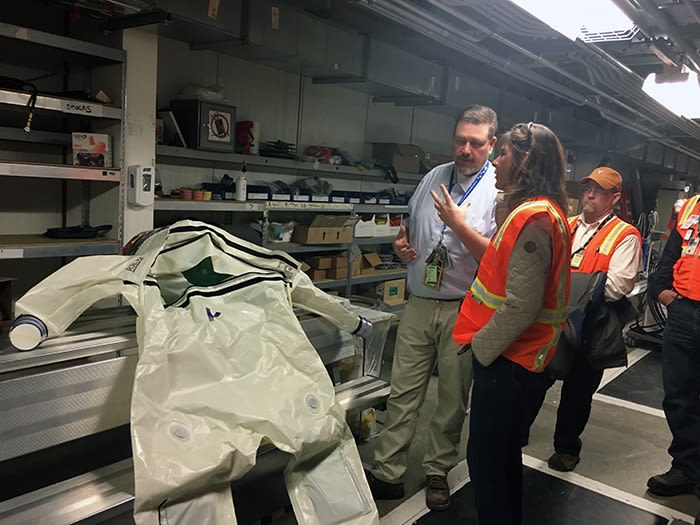

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, located near Carlsbad, N.M., is the nation’s only underground repository for disposal of defense-related transuranic waste. This material – often clothing, tools, and debris from other Department of Energy facilities —has a radioactive half-life of more than 20 years. WIPP resumed operations in 2017 after an extended recovery from an underground vehicle fire and subsequent radiation release in February 2014.

The History

The history of WIPP can be traced to 1957, when the National Academy of Sciences endorsed underground salt formations for disposal of radioactive waste, as salt tends to be found in stable seismic areas with little risk to groundwater. The Energy Department selected southeastern New Mexico for this purpose, and WIPP opened in 1999.

Since then, the repository has received over waste 12,000 shipments from more than a dozen DOE sites. It held 92,162 cubic meters of transuranic waste at the start of 2018. Minus roughly 400 cubic meters of remote-handled TRU waste, the material is all contact-handled material that has a lower radioactive dose, according to the Energy Department’s fiscal 2019 budget justification.

Today

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant today is managed by Nuclear Waste Partnership, an AECOM-led partnership with BWX Technologies and major subcontractor Orano (previously AREVA Federal Services). Its current $2 billion contract runs through September 2020.

CAST Specialty Transportation has an indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract for waste hauling, which runs until May 2022. The deal has an estimated value of up to $112 million.

The site is regulated by the New Mexico Environment Department and three federal agencies: the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Transportation, and the Labor Department’s Mine Safety and Health Administration.

With the resumption of waste emplacement in early 2017, the mine last year first took in waste that had been stranded above-ground at WIPP since the accidents, along with 133 shipments from around the DOE complex. The agency and its contractor estimate the site will receive about 300 shipments during the 12 months from February 2018 to February 2019.

As ventilation levels have increased, WIPP in January 2018 resumed salt mining to increase disposal space.

Workers are emplacing waste in storage Panel 7, which is expected to be filled in 2020. Mining is underway in Panel 8. The underground facility is currently licensed by the state for 10 panels and will eventually have to seek authorization for more panels.

Underground airflow at WIPP must be increased to the point where workers can simultaneously conduct both full-scale waste emplacement and salt mining. That will require increasing the current underground airflow of 140,000 cubic feet per minute by installing a new permanent ventilation system to eventually generate up to 540,000 CFM.

The $403 million WIPP budget request for fiscal 2019, which begins Oct. 1, includes $84 million for the ventilation system, which also received $86 million in the final 2018 budget. The system has been designed and is intended to come online around 2021 at an estimated cost of $273 million. Nuclear Waste Partnership is reviewing bid proposals for the ventilation project and hopes construction will start by summer.