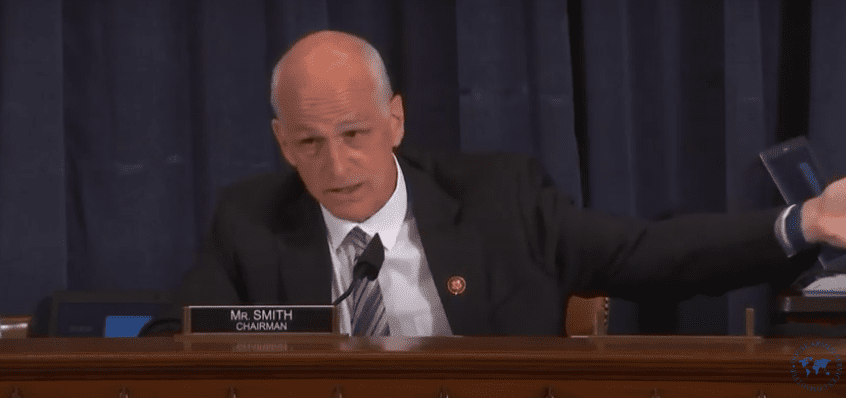

The Department of Energy’s plutonium-pit production plant in South Carolina would get a little extra scrutiny, and civilian nuclear weapons programs would receive a little more funding than requested, under the major defense policy bill approved unanimously…