Southwestern host states probably cannot stop construction of temporary spent-fuel depots in their territories by arguing that licensing such sites is against federal law, a couple of retired nuclear policy hands opined this week.

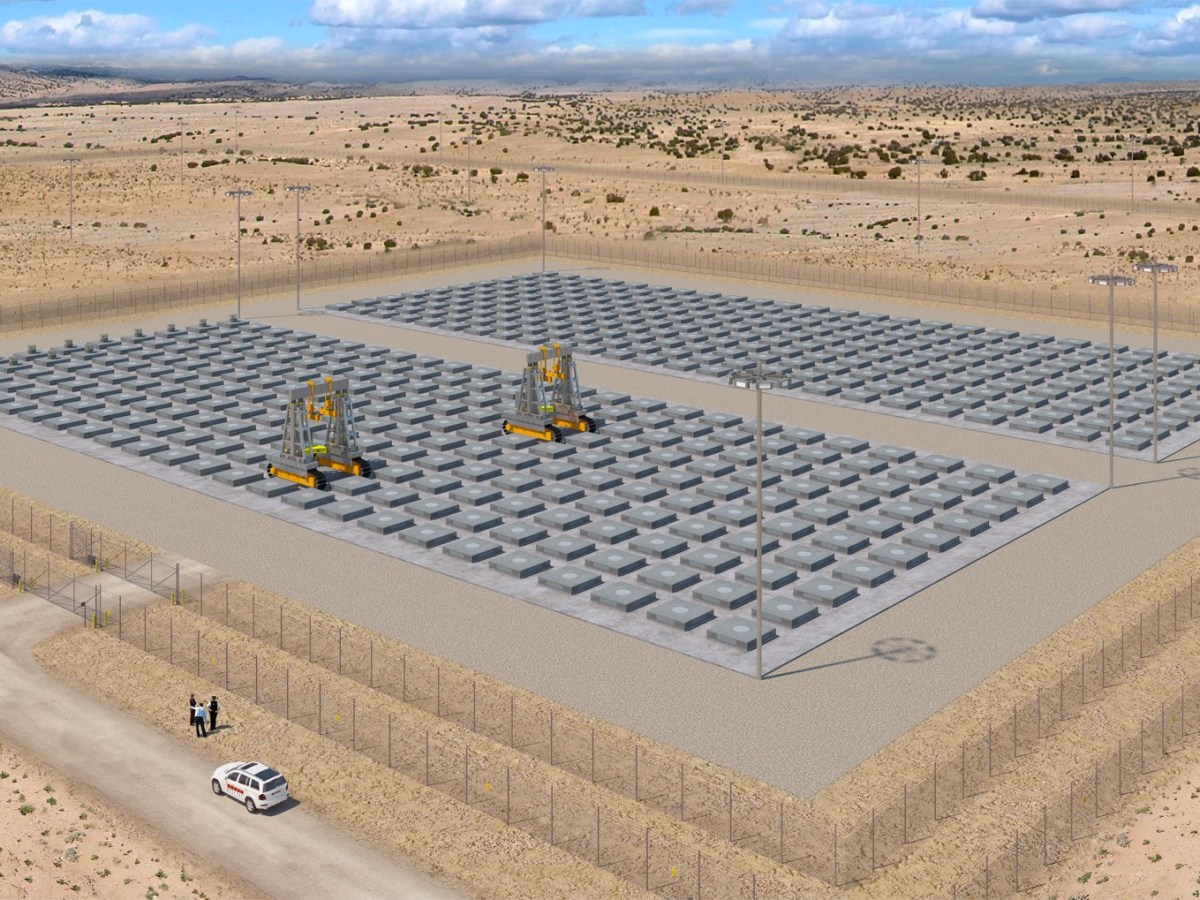

Pending a few more reviews, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission could license Interim Storage Partners’ proposed commercial interim storage facility in west Texas by September and a similar site proposed by Holtec International in southeastern New Mexico by January. If built, the privately operated sites would become the only places in the U.S. able to consolidate — not indefinitely — spent fuel from multiple power plants.

To block the licensing and subsequent construction of these interim storage facilities, Texas and New Mexico have seized on the same argument: that the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) forbids construction of an interim storage site until there is a permanent nuclear-waste repository — something that has seemed out of reach since the Barack Obama administration decided not to proceed with Yucca Mountain.

Members of the Texas House of Representatives made the NWPA argument in a general way in a July letter to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. New Mexico has put a much finer point on things, filing suit against the NRC in the U.S. District Court for New Mexico and alleging, among other things, that the commission’s drive to license a commercially operated spent-fuel site “violates and runs counter to the underlying purpose and Congressional intent of NWPA.”

“It’s just not accurate,” former Rep. John Shimkus (R-Ill.) told RadWaste Monitor in a phone interview on Tuesday. “The Nuclear Waste Policy Act does not prohibit private interim sites.”

Shimkus was a self-described “nuclear waste guy” on Capitol Hill during a 24-year run in the U.S. House of Representatives that ended earlier this year. He’s now a principal at St. Louis-based lobbying and consulting firm Kit Bond Strategies, which serves the nuclear energy industry, and a part-time teacher at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

In his second-to-last term, Shimkus’ 51-page Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 2018 made it through the House on a bipartisan vote but died in the Senate without debate. It was the deepest legislative push of any major nuclear-waste reform since President Bill Clinton vetoed a package of similar scope more than 15 years earlier.

Like Shimkus, ex-Department of Energy official David Klaus told the Monitor this week by phone that the NWPA “is not applicable to the licensing of a private consolidated interim storage facility” by the NRC, which derives its authority from another part of federal law, the Atomic Energy Act.

On the other hand, the former DOE deputy undersecretary for management and performance said, the NWPA “clearly says” the federal government cannot make its own interim storage site “before they license a long-term repository.”

The NRC itself reminded the public about the agency’s legal prerogative to okay a commercial interim storage depot this week, hitting back against claims in Balderas’ District Court lawsuit in an Aug. 17 filing.

“[L]icensing of the CISF facilities by private parties is governed by the [Atomic Energy Act], not the NWPA,” the commission wrote.

In a footnote in its Aug. 17 filing, NRC called out a 2004 opinion by the D.C. Circuit Court in which appellate judges, reviewing the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 1982 and a congressional report accompanying the bill, wrote that “[n]othing in those reports and debates suggests that Congress intended to prohibit private use of private away-from-reactor facilities.”

Private use of private facilities is, Klaus thinks, probably what commercial interim storage sites would settle for, if any are built in the very near future.

“The more relevant current legal question is whether the feds can take possession of spent fuel and pay the costs associated with storing it at a privately run storage facility,” Klaus told the Monitor. “[T]he consensus seems to be that the answer to this question is ‘no.’”

Supporting his interpretation, Klaus pointed to Congressional efforts in recent years that would have changed the law to let DOE assume title to spent nuclear fuel and plop it down in a facility like the ones Holtec and Interim Storage Partners have proposed.

Shimkus’ 2017 legislative opus, for example, would have directed DOE to figure out how to take ownership of spent nuclear fuel and store it in a facility operated by “non-Federal entities,” according to the report for the bill.

Balderas is aware of that, too.

In his lawsuit for New Mexico, the state attorney general wrote that it would be “commercially infeasible” for privately operated interim storage sites to expect owners of spent nuclear fuel to “retain title and responsibility (including insurance) for the transport of high-level and high-risk nuclear waste after the closing and decommissioning of their respective reactor and/or independent spent storage installation facilities.”

At deadline, the judge in the New Mexico suit had yet to rule either on Balderas’ request for a declaratory judgement, which would block the NRC license for Holtec, or the NRC’s motion to throw Balderas’ suit out of court.