Weapons Complex Monitor Vol. 34 No. 35

Visit Archives | Return to Issue PDF

Visit Archives | Return to Issue PDF

Weapons Complex Monitor

Article 1 of 11

September 15, 2023

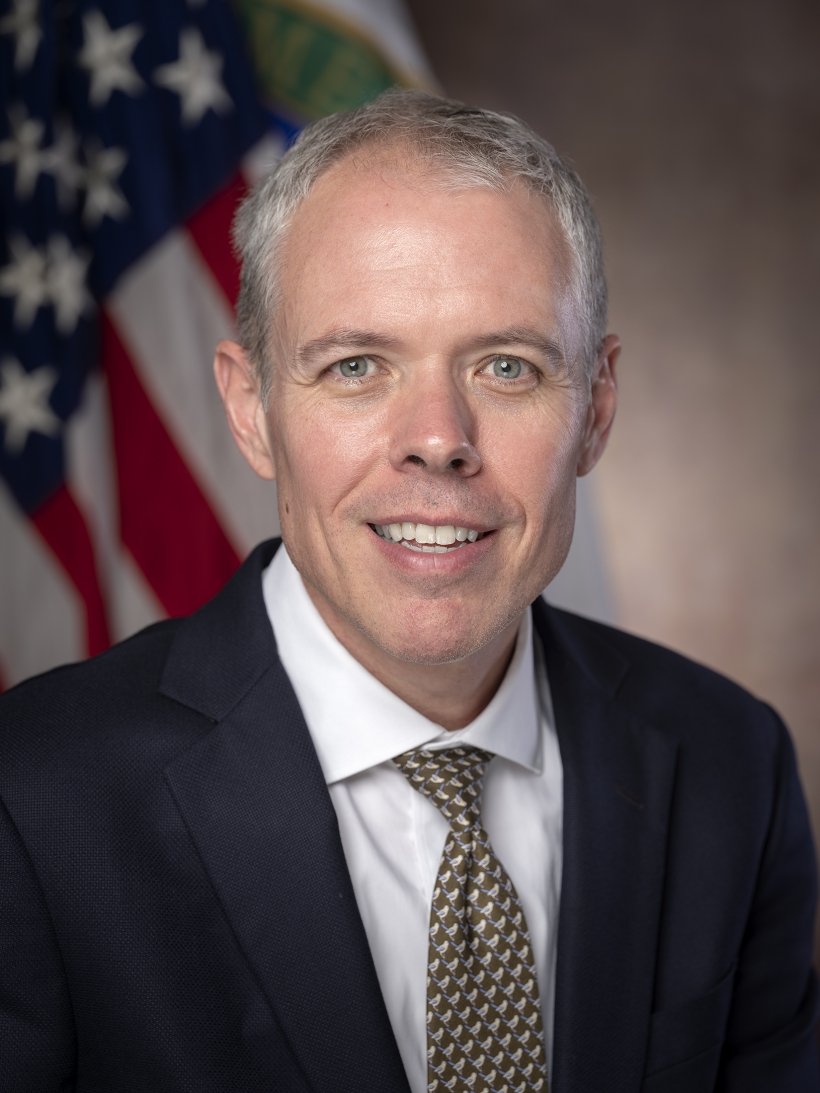

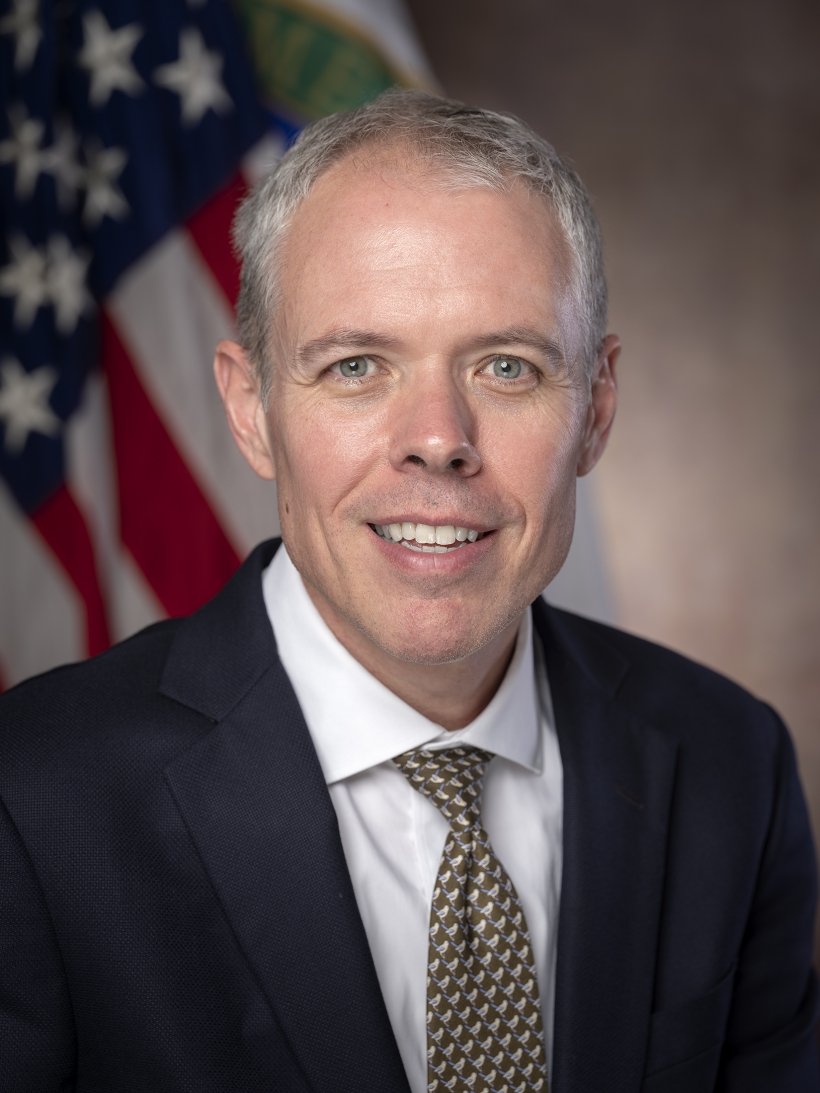

Cleanup boss White ponders telework but not retirement

ARLINGTON, VA. — While many senior people are contemplating retirement at the Department of Energy’s $8-billion Office of Environmental Management, William “Ike” White apparently is not among them.

“No. I do not have a retirement date circled on my calendar…

Partner Content

Jobs