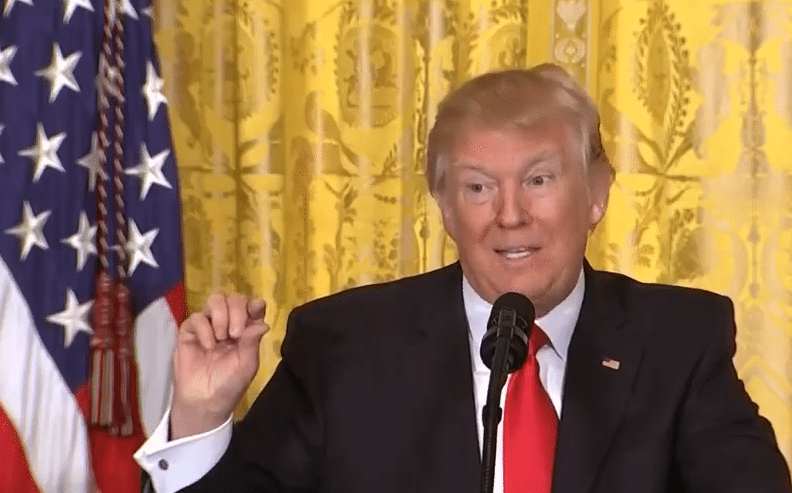

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of quarterly news summaries and analyses about President Donald Trump’s first 100 days in office. We’ll check in with one long, big-picture update every 25 days, with a regular flow of updates in between to keep you up on news affecting U.S. nuclear cleanup during the new administration’s crucial first days.

We’re a quarter of the way through President Donald Trump’s first 100 days office, and the nuclear-cleanup clique might have noticed a dearth of permanent leadership at the Energy Department.

Two months after he was formally nominated, former Texas Gov. Rick Perry has yet to receive Senate confirmation as energy secretary. This has delayed the swearing in of lower-level DOE appointees such as the next head of the Office of Environmental Management (last rumored to be Gary Lavine, the former DOE attorney, lifelong GOPer, and ardent Trump convert who flew the flag proudly for his fellow New Yorker at the GOP nominating convention last year in Cleveland).

At the moment, Perry’s confirmation appears to be a matter of when, rather than if. The nuclear-friendly former governor is last on a list of six remaining Trump Cabinet nominees due for a floor vote, and while his nomination has not been particularly controversial so far, Senate Democrats have stridently opposed some candidates who are ahead of Perry in the queue. Senate rules still allow the minority the opportunity to throw up significant procedural hurdles to these other nominees, which could delay a vote on Perry until perhaps the end of February.

Meanwhile, Trump did make some nuclear-notable leadership changes during his first 25 days in office, including rearranging the hierarchy of the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board by installing Republican members Sean Sullivan and Bruce Hamilton as chairman and vice chairman, respectively. The overall membership of the five-person nuclear watchdog group — known well for its conservative (read: risk averse) approach to the DOE complex — remains the same.

In the aggregate, then, the first 25 days of the first 100 days of the new Trump administration have passed relatively quietly. Major Cold War cleanup procurements that began before Inauguration Day — including for prime contracts at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the Paducah Site in Kentucky — have rolled on with only “minor delays,” one industry official said.

Until the Senate confirms Trump’s chosen energy secretary and allows the other leadership dominoes at DOE to fall, the U.S. nuclear-waste enterprise will remain in the holding pattern it entered almost a month ago.

On one hand, this holding pattern allows departmental landing teams from the new administration to smooth the way for their future boss, cataloging their DOE policy challenges and acculturating themselves to the quirks of their new agency home in relative privacy. On the other hand, appointee holdovers from the previous administration and apolitical career civil servants have had to fill the leadership vacuum at DOE, resulting in a kind of stay-the-course technocracy that — depending on your angle — is either essential for an agency’s long-term stability, or the nefarious wheedling of recalcitrant sore losers and the unelected deep state.

Again, depending on where you sit, you might detect one or the other of those down at the Savannah River Site in Aiken, S.C., where according to one source, a senior official appointed by then-President Barack Obama to the National Nuclear Security Administration is pressing lawmakers and the Trump administration to shut down the Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility being built by CB&I AREVA MOX Services.

The Obama administration wanted to use an alternative method for disposing of 34 metric tons of weapon-usable plutonium, sending the material to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico for permanent underground disposal; adherents to this particular wisdom are still pulling paychecks at NNSA, where Obama appointee Frank Klotz is expected to stay on as administrator for most of Trump’s first 100 days.

Fairly or not, big capital projects that are over budget and behind schedule can stand out like neon signs to new presidential administrations eager to make their mark on the federal government.

On a related note, the Senate on Thursday confirmed Rep. Mick Mulvaney (R-S.C.) as director of the White House Office of Management and Budget: the executive organ that tells federal agencies what programs the president believes they can and cannot afford to pay for every year.

The staunchly conservative Mulvaney generally favors budget cuts for everyone, including defense programs. That said, he has voted for more than half of the last 10 appropriations bills signed into law and isn’t known for picking fights over nuclear waste. In fact, he has supported MOX and last year sponsored a bill that would have helped privatize interim storage of commercial nuclear waste.

In other 100-days news, there was no sign that DOE’s nuclear programs were subject to the sort of blanket communications blackout the Trump administration imposed on other agencies after Inauguration Day, such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Agriculture.

The Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board’s website went incommunicado for about a week after Jan. 21 as the independent nuclear watchdog retooled and relaunched its online portal, but career civil servants there and at DOE continued answering their phones (and even sometimes emails), saying privately that little had changed for them, other than a few new names in the chain of command.

Another nationally covered Trump order, the regulatory freeze put in place during the new President’s first week in office, touched at least one federal rule-making related to DOE: one that clarifies the agency may seek civil penalties against contractors that try to intimidate whistle blowers within their ranks. The rule now will go into effect March 21, pending approval by the Trump administration. It was previously to take effect Jan. 26.

On the whole, however, the DOE nuclear enterprise, like many other federal agencies, is still waiting its turn for the wonky Washington action that will set the stage for the Trump administration to at last lay its hands on the agency’s legacy nuclear-cleanup machinery. The latest cost estimate from the Government Accountability Office puts the cost of remaining cleanup work at more than $250 billion.

As career officials at the Energy Department wait for their new boss to arrive, questions from the Trump transition team lurk in the wings at DOE.

Looming large is the administration’s search for a practical long-term plan to pay for cleanup of former uranium enrichment facilities at DOE’s Portsmouth and Paducah sites, which now is funded largely through the dwindling Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund. The Obama administration solution, to plug the shortfall with a new tax on nuclear power companies, no more jibes with the Trump administration’s antiregulatory bent on Day 25 than it did on Day 1.

The Portsmouth Site in Ohio in particular has started to paint a target on its back, announcing what could be as long as a six-month slip for a crucial milestone toward demolishing the radioactively contaminated X-326 process building. Fluor-BWXT Portsmouth has acknowledged the building might take until December to go cold and dark — isolated from electricity sources in preparation for tear-down — instead of June.

Elsewhere in the Environmental Management enterprise, there are old sales pitches to rehash for new political appointees. The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant offers a prominent example.

Leave aside for the moment the possibility that the Trump administration could direct DOE to send tons of diluted plutonium to the deep-underground transuranic waste facility in the distant future. In the here-and-now, WIPP boosters have to sell new DOE appointees on the idea that the remaining $50 million or so the federal government owes New Mexico under the 2016 settlement that cleared the way for the mine to reopen in December 2016 should not come out of WIPP’s annual operating budget of roughly $300 million. WIPP proponents including Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) fought that battle last year when Congress was rushing to pass a stop-gap spending bill to keep the federal government running through April.

There is little evidence so far about what the Trump administration thinks about any of these problems. Perry was cagey during his nomination hearing before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, and the administration has not replied to requests for comment about the issues lurking in the weeds — or the salt, in WIPP’s case — across the DOE nuclear complex.

There are of course the words of the energy secretary-designate to mull over while we wait for a confirmation vote. Offered in reply to a question from Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) about what that lawmaker characterized as an illogical approach to nuclear cleanup in his state under the Obama administration, they offer one of the only public insights so far into Perry’s philosophy for DOE, writ-large.

“Without knowing the deep details of this … my instinct tells me that this is an issue of execution, of good management,” Perry said.