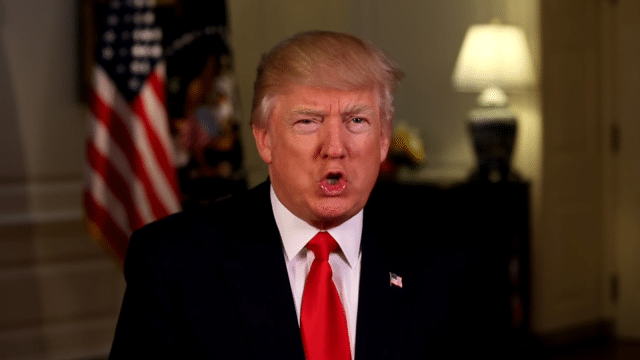

With more of President Donald Trump’s first 100 days in office gone than remaining, the Energy Department’s Cold War cleanup contractors find themselves — comfortably for now — in the eye of a political storm, shepherded through a prolonged lack of permanent agency leadership by veteran DOE managers.

It has been almost a month since former Texas Governor Rick Perry was sworn in as the 14th secretary of energy, and in that time the White House has not nominated a second-in-command for Perry, let alone an assistant secretary for environmental management to head the agency’s legacy nuclear cleanup.

One source close to the White House, who has served at DOE, said the Trump administration balked at Perry’s request to hire 20 people of his choosing for senior Energy Department positions. While much has been made of Trump’s preference to hire only people loyal to him, his is not the first administration to weigh whether Cabinet secretaries ought to be able to bring on their own people.

As it happens, Perry already has one of his own at DOE: his deputy chief of staff and former presidential campaign aide Dan Wilmot, who joined the new energy secretary on a trip to Yucca Mountain in Nevada this week while Brian McCormack, Perry’s chief of staff and a former White House aide in the George W. Bush administration, stayed behind in Washington.

So for now, and at least until the White House appoints a deputy energy secretary, that leaves Sue Cange as the acting assistant administrator for environmental management. A well-respected veteran of the department’s Office of Environmental Management (EM), Cange has so far kept the wheels from coming off the wagon at EM, and kept the ripples in the weapons complex’s business rhythm to a minimum.

That, according to some industry representatives who spoke privately with Weapons Complex Monitor, is just fine with the contractor community. Cange is a known quantity with a long history at EM, where she previously managed the office’s Oak Ridge, Tenn., branch.

Parenthetically, there has been no indication that Rick Dearholt, the former Jacobs Engineering hand who earlier this month said he landed a job interview to lead the Environmental Management office, will be called on to replace Cange anytime soon. Reached Thursday, Dearholt told Weapons Complex Monitor he has had no contact with the Trump administration since DOE canceled his job interview a few weeks ago, and that he could not comment on the White House’s strategy for filling vacant leadership positions at the department.

This period of relative calm will not last forever, but while it does, industry has apparently faced only minimal business disruptions. Awards of at least two major cleanup jobs are tracking on or close to the schedule EM roughed out when it solicited bids in mid-2016: deactivation and remediation of the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Paducah, Ky.; and liquid waste management at the Savannah River Site near Aiken, S.C.

Of course, even in years when the entire federal government is not ponderously repositioning itself after a transfer of power at the highest level, the dates inked into a final solicitation might not link up exactly with contract awards that routinely happen six months after bids are due. But in a year when the entire executive branch performs an ideological backflip and fiscally conservative political operators are given free reign — and plenty of encouragement — to slash the federal budget wherever possible, it is practically a given that any plans to send hundreds of millions of tax dollars into the private sector will face schedule-altering scrutiny.

Take the 10-year Paducah contract, for example. DOE expected to start transitioning the work over to a new contract from incumbent Fluor Federal Services on March 23. A transition period usually follows a public announcement of a contract award. At the time of this writing, more than a week after the expected transition start, there has been no such announcement.

A representative for one firm that bid on the Paducah work said this week that the company has received neither a notice of an award, nor a “thanks-for-playing” debriefing about why its proposal was not selected.

The effect of the new administration on the Savannah River Site contract was harder to judge at deadline for Weapons Complex Monitor, as DOE did not expect to start transitioning to the new contractor until April 2. Among the known bidders for that 10-year deal are AECOM, BWX Technologies, and Fluor Corp. Fluor is said to have teamed with Westinghouse for its bid. That company, part of the financially embattled Japanese conglomerate Toshiba, rocked general circulation news this week when it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

A Westinghouse spokeswoman on Thursday noted that Westinghouse Government Services, which she acknowledged is rumored to be part of the SRS liquid waste bid, is not one of the debtors in the parent’s Chapter 11 reorganization.

Fluor and Westinghouse are also working together to install four new Westinghouse reactors at nuclear plants in South Carolina and Georgia. In a financial disclosure this week, Fluor assured investors that work would continue. As for the effect on other nuclear-focused partnerships, Irving, Texas-based Fluor has been mum.

Hovering over the personnel intrigue in Washington and the slight, though perceptible, grinding of gears at DOE’s acquisitions shop, is the Trump administration’s radical budget proposal. Under the so-called skinny budget released earlier this month — one of the most significant EM policy turns of the president’s first 100 days in office so far — EM would get $6.5 billion for fiscal 2018. Adjusted for inflation, that would be the biggest EM budget in almost 10 years.

As ever inside the Beltway, the devil will be in the the details. The administration’s budget blueprint was long on greatness but short on the specifics of making it so. The White House has said it will unveil its full budget proposal in May — technically after Trump’s first 100 days in office (unless the proposal arrives May 1).

So far, all that is known about the administration’s plans for EM in 2018 and beyond is that they will “advance the Environmental Management program mission of cleaning up the legacy of waste and contamination from energy research and nuclear weapons production, including addressing excess facilities to support modernization of the nuclear security enterprise,” according to the skinny budget.

The last bit has left some scratching their heads, parsing the language for signs that it signals a fresh set of responsibilities, and bills, for EM.

Perhaps, as Seth Kirshenberg of the Energy Communities Alliance speculated at the time the budget blueprint dropped, the White House planned to give EM responsibility for cleaning up facilities the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) is no longer using for active nuclear weapons programs.

“This is a large budget item that would free up more funds for NNSA while creating more costs for EM,” Kirshenberg said.

That would require congressional buy-in, and EM does not lack for allies on Capitol Hill who chafe at sidelining funding from already-overtaxed cleanup projects for any purpose.

A lot can change in 100 days, but probably not that.